There's hardly any piece in the operatic repertoire as enigmatic as Virgil Thomson's Four Saints in Three Acts. You can read Gertrude Stein's libretto here, but you might need a stiff drink.

The writing has been called "verbal nonsense" or merely that Stein was more interested in the sounds of words than what they meant. Thomson's score is a collage of non-operatic American styles - hymns, marching band, parlor tunes - and he described the piece himself as "virtually a complete summary of my Protestant childhood in Missouri." His musical life was indeed colorful, and in by the age of sixteen he could be found accompanying silent films on the piano and Baptist choirs on the organ in the same week.

It may be interesting to note that it originally featured an all-black cast (who apparently had the clear diction Stein desired), and premiered in 1934, the same year as Cole Porter's Anything Goes!

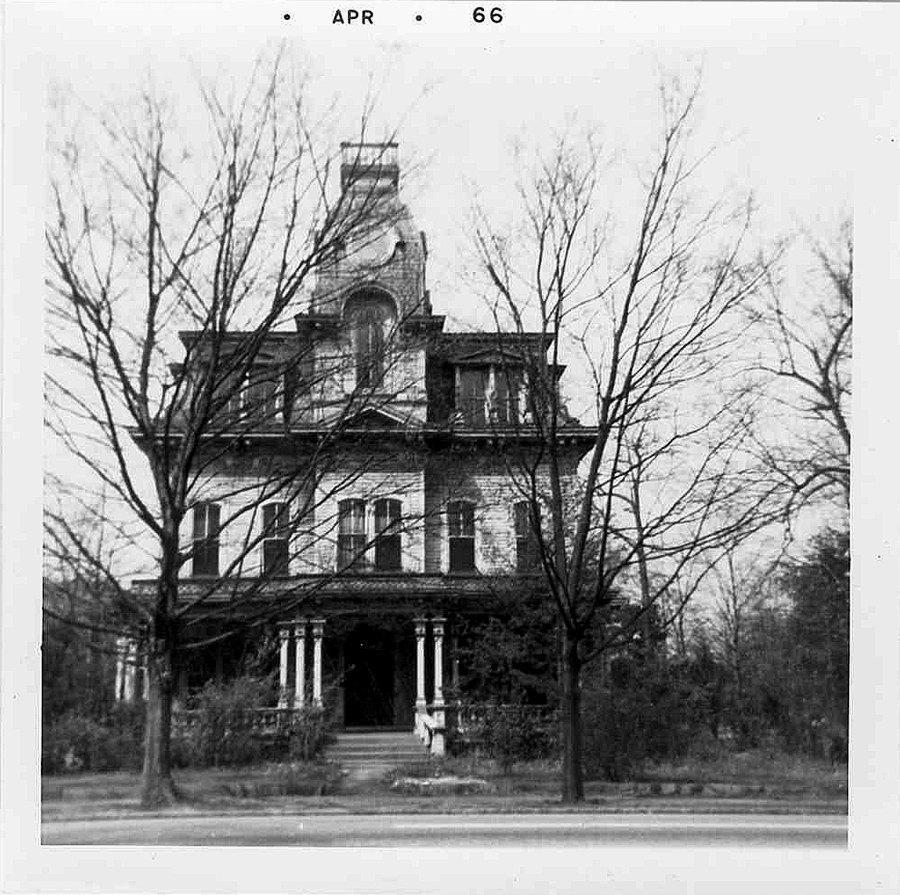

|

| An image from Thomson's original production |

We are lucky to have two very different artists weigh in on how to approach this challenging work. The first is Mary Birnbaum, who directs both theatre and opera and also serves as the Associate Director of the Artist Diploma in Opera Studies Program at Juilliard.

Our next post will feature the writing of Andrea Andresakis, who takes a very different approach, but no less interesting.

Mary worked with a team of designers to dream up these great ideas:

--

We searched for a way to present the show that would be as dissonant in a contemporary context as the original staging was in its own time. In trying to rebel against Stein and Thompson, we wound up using what they were rebelling against: the American theater of the 1930s: representational, beautiful and divorced from the audience. Our production of Four Saints in Three Acts will slam the theatrical conventions of the 1930s -- Follies divas, historical tableaux vivant and religious pageantry -- up against the efforts of Stein and Thompson, turning their rebellion on its head and creating a new, exciting dissonance.

On stage is a proscenium theater wherein the scenes from the lives of the saints are playfully depicted, replete with charming historical inaccuracies. This is a church of art, where chorus girls and boys portray saints and collaborate with stagehands to create a show and inspire the suspension of disbelief; theatrical magic stands in for divinity. As Stein and Thompson point out, saints and artists have a lot in common: both try to share their visions and encounter problems when others doubt their convictions. Both feel out of sync with the conventions of their time yet attempt to connect with a type of timeless truth.

There's even an onstage audience for the play, an elderly couple (the Commère and Compère) who are constantly trying to make sense out of the nonsense in front of them, rifling through their programs to try to find out what scene they’re watching. We watch the Commère and Compère watch a play, but also we are aligned with them, delighted to find that we share their perplexed, outsider reactions from time to time.

The staging begins as a tightly ordered machine, highly choreographed and representational. The ensemble saints earnestly replay St. Teresa’s life in Avila, avoiding camp but occasionally stumbling into the ridiculous. Gradually, however, the rules and norms of the 1930s theater stop working, and the abstract starts to take over in an unexpectedly beautiful way. As scenes progress, no set piece is ever struck, the vines of the garden become bedecked with stars. The established order is so confused that audience and artists alike are forced to join Stein and Thompson in their celebration of the essential illogical nature of art, life and God.

Even the strict boundary between actor and audience dissolves; the Commère and Compère ecstatically find themselves on the stage and some of the showgirls wind up in the actual opera house. The houselights come up to reveal humanity everywhere. We concede that things can both be and not be, that the divine both is and is not a “fact".

The prologue of the piece is played downstage of a drop that shows the outside of the theater on stage left and the stage door on stage right. As we are told, to orchestral oom-pah-pahs, what's going to happen, we see a continual stream of bundled up chorus girls enter the stage door in time for half hour call and then fancy fur-clad audience members enter the theater.

Finally, the Marquee lights up, reading "FOUR SAINTS IN THREE ACTS" and the performance is ready to begin, the drop flies away and we are looking at the house of the theater, where the Commère and Compère have bustled to their seats in a convenient balcony, opera glasses in hand and sucking on sugar free candy. As they wait for the houselights to dim, they read each other the cast list aloud, "saint... saint... saint..." trying to keep track of "who's who". At the end of the prologue, the curtain inside the smaller proscenium opens on the steps of Avila Cathedral, and the real show begins.

Learn more about Mary Birnbaum's work at www.marybirnbaum.com